Download Resources - English

- Tool J_Country Risks and Impacts_EN.xlsx

- Tool I_Local Security and CT Incidents_EN.xlsx

- Tool H_Local Security and CT regulations_EN.xlsx

- Tool G_SCTM Organisational Impact_EN.xlsx

- Tool F_Banks Overcompliance Incidents_EN.xlsx

- Tool E_Procurement Overcompliance Incidents_EN.xlsx

- Tool D_Donors Requirements Incidents_EN.xlsx

- Tool C_SCTM Problematic Clauses_EN.xlsx

The impacts of sanctions and counterterrorism measures: Data collection toolkit

5. SCTM-Related issues

Screening obligations

Due diligence involves a series of initial assessments carried out by an organisation to ensure that the entities it intends to engage with have the necessary procedures in place and are sufficiently trustworthy to receive funds or resources without misuse or causing harm. This process encompasses many precautionary practices, such as organisational audits, examinations of financial records, and ethical and criminal background checks.

Within the realm of due diligence, screening - also referred to as vetting - largely originated from requirements set by institutional donors, starting in the 2010’s. This came in response to heightened vigilance by UN Member States regarding terrorism financing and money laundering risks. The adoption of sanctions regimes and counterterrorism

laws and measures (SCTM) by States is subsequently enforced by governmental agencies and frequently translated into specific clauses of donor agreements. Typically, SCTM feature lists of designated individuals and entities, forming the

basis for screening.

Consequently, an increasing number of humanitarian organisations are incorporating this process, often utilising specialised software that enables screening based on the origin of the lists. These organisations also implement specific

internal policies detailing the scope, range and process for each category of screening targets. Most organisations screen their suppliers, contractors, employees, and other NGO partners such as trustees and directors.

Screening persons in need of humanitarian assistance, who are the inherent recipients of the organisation's resources, is viewed as a red line most humanitarian NGOs won't cross. Critics argue that screening based on criteria unrelated to

humanitarian needs breaches IHL’s fundamental impartiality principle, and may create severe risks for humanitarian staff and operations.

Moreover, beyond concerns about data protection and security, inputting names into a screening system might infringe upon an individual's right to privacy. Even if permission is granted, the context in which consent is obtained - often when

individuals are in desperate need for assistance - raises questions about their informed consent’s authenticity.

The overall effectiveness of screening is a topic often debated due to the following reasons:

- The challenge of cross-referencing third parties across multiple designation lists (e.g., UN, US, EU).

- The low number of valid matches compared to the substantial administrative workload it

entails. - The ease with which listed entities can evade detection by using front organisations or nominees.

Why do we collect this information?

To uphold neutrality, the humanitarian sector avoids endorsing or opposing the rationale underlying SCTM. Consequently, advocacy efforts avoid challenging the overall validity of designation lists as counter-terrorism instruments. Instead, the

approach involves highlighting the bureaucratic challenges that these measures pose to humanitarian operations. The intention is to foster collaboration with Member States and their agencies, aiming to find pragmatic solutions that adhere to international regulations while minimising disruptions in high scrutiny environments. This data collection

framework aims at:

- Illustrating the time and resources currently dedicated to screening

- Putting things into perspective by comparing numbers of positive matches VS screened entities (proportionality)

- Examining the impact of false positives on operational efficiency. Aligned with the ethical standards of its designing

organisations, this data collection framework will not cover the question of beneficiaries screening, except in cases of third-party screening, - such as that conducted by money transfer agencies in cash-based activities.

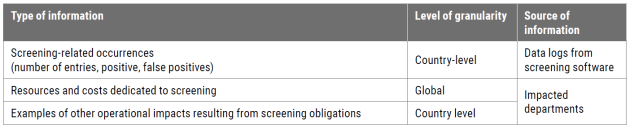

What information do we want to collect?

Beyond its application in advocacy efforts, data concerning screening obligations offers minimal value to both operational and support teams. Hence, quantitative data will be sourced from the logs of each organisation's screening software. This information will be further complemented by targeted interview questions posed to the impacted departments.

Tool G: SCTM Organisational Impact

Type: Survey

Tab: Procurement, HR, Partnerships

Tool J: Country Risks and Impact

Type: Survey

Tab: Procurement and Partnerships

Donor requirements and contractual clauses

The contractual clauses mandated by institutional donors who fund both humanitarian, stabilisation and/or development programmes, exemplify the ramifications of SCTM on humanitarian operations. The process of negotiating and implementing these clauses carries significant implications for organisations and their programmes. It is important to

highlight that these clauses vary considerably depending on the specific financing instrument employed and the normative framework to which it is tied.

Why do we collect this information?

Aggregating information about contractual clauses imposed by both institutional and private donors offers several benefits to organisations:

- Identifying potentially problematic clauses and engaging in dialogue or negotiation with donors.

- Identifying the most challenging donors, aiding efforts to standardise practices across organisations in affected areas.

- Documenting the impact of problematic clauses on programmes, streamlining operations, and fostering advocacy efforts.

- Analysing changes in the wording of proposed clauses and comparing requests from different donors to provide insights for donor’s engagement.

By conducting a thorough analysis of these contractual clauses, advocacy efforts can be directed towards States or international/regional bodies such as the UN or EU, enforcing sanctions regimes, with the ultimate goal that these clauses clearly respect principled humanitarian action.

How can it be directly useful to operations?

Taking stock of clauses linked to sanction regimes, along with instances of contractual incidents and problematic clauses that impose strict compliance with sanctions, anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist measures, serves several crucial purposes for operations:

- Supporting the identification and negotiation of clauses that might conflict with the organisation's values or humanitarian principles, such as screening final beneficiaries.

- Preventing – to some extent – the potential risk of expenditures being deemed ineligible during audits. This will protect the organisation's reputation and secure future funding opportunities.

- Quantifying the risks that the organisation currently faces due to unrealistic contractual commitments (physical impossibility, security concerns for teams/programmes, changes in activities or areas, etc).

Moreover, active involvement in global advocacy efforts on this matter by donor relations and operations departments, both at the head office and in the field, can alleviate the negative impact of sanctions and counter-terrorism measures,

thereby facilitating humanitarian work.

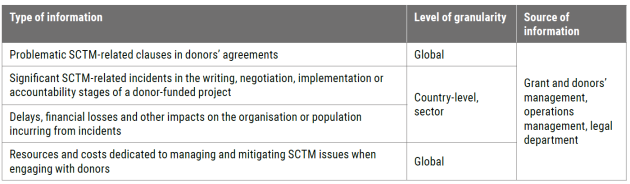

What exactly do we want to collect?

" […] all recipients of project funds need to be vetted and cleared against EU sanction lists and no payment

can be released to any company or individual in case of any concern or inclusion on that list".

In the early 2020s, a few French humanitarian organisations observed a growing challenge with funding contracts from certain donors. These contracts included clauses that mandated the screening of stakeholders, including, in some instances, the final beneficiaries, to ensure their absence from sanctions lists. Through a

comprehensive analysis of these clauses and their potential impacts, a global advocacy initiative was undertaken. Its aim was to oppose beneficiary screening, in line with humanitarian principles, and to seek guarantees from donors and governments against its implementation.

Tool C: Problematic Clauses in Donor Agreements

Type: Register

Tool D: Donors’ Requirements Incidents

Type: Register

Tool G: SCTM Organisational impact

Type: Survey

Tab: Grant

Tool J: Country Risks and Impact

Type: Survey

Tab: Grant impact

Private sector de-risking and overcompliance

The FATF1 defines de-risking as “the phenomenon of (financial) institutions terminating or restricting business relationships with clients or categories of clients to avoid, rather than manage, risk”. Entities that choose to de-risk often do so because they perceive the client’s exposure as excessively high, particularly when they have insufficient knowledge about its operations in sanctioned areas.

By extension, overcompliance encompasses all risk limitation practices, including due diligence precautions, that go beyond what is strictly necessary or required by the SCTM normative framework. Deterring actions may include practices such as “cumbersome, onerous documentation or certification, charging higher rates […] or imposing discouraging long delays”.

This trend is primarily observed in financial transactions. Organisations frequently experience transfers being temporarily halted or even cancelled by banks for compliance reasons. These incidents are not always solely linked to the bank

mandated by the organisation: a single wire transfer can involve multiple financial intermediaries (sometimes 3 or 4) between the originating and recipient banks. These middle entities, often unaware of the initial transaction details beyond basic ledger information, might block a transfer without prior consultation. Consequently, organisations can see their transfers returned without receiving detailed justifications. Even when organisations pinpoint the troublesome intermediary, its legal and compliance teams may still be reluctant to engage in any form of communication.

Instances of SCTM-related overcompliance or de-risking have also been observed in other private sectors. Many organisations have reported incidents with suppliers and contractors. They may manifest as a reluctance to submit bids or through the unjustified use of suspensive agreement clauses.

Derisking action by a bank: "TrustBank", a prominent UK bank, has traditionally managed funds transfers for NGO “X” concerning projects in Sudan. However, heightened regulatory concerns about counter-terrorism financing prompted "TrustBank" to conduct a thorough assessment of its operations and client base.

Initially, the bank halted NGO “X”'s wire transfers to sanctioned countries, including Sudan. Eventually, it unilaterally severed ties with the NGO, labelling it a “high-risk” client.

Overcompliance by an international supplier: NGO "Z", operating in Syria, invited bids from global computer vendors. "CompGlobal" emerged as a top contender but withdrew due to concerns about potential legal SCTM issues, failing to communicate this decision to the NGO. After multiple follow-up calls, NGO "Z" finally reached

"CompGlobal's" legal team and reverted their decision by justifying the intended purpose of each computer (which translated into 7 days of work for the procurement team).

Overcompliance and de-risking strategies over SCTM have several consequences for organisations:

- Workloads and delays: To meet compliance requirements and establish trust with third parties, organisations often find themselves needing to provide extensive information, such as detailed project lists, explanations of fund usage, donor letters, and relevant licenses. This process demands a significant investment of both time and resources.

- Compromised alternatives: Instances of denied transactions or services compel organisations to seek emergency fallback options, typically leading to subpar results that might compromise the quality of humanitarian interventions. Specifically, bank de-risking could push humanitarian groups towards informal money or value transfer agencies

(MTAs), introducing further compliance challenges. - Disruptions: The cumulative effect of the above consequences can trigger a chain reaction and systemic backlogs. This situation may result in the suspension of activities, with no immediate viable alternatives. Furthermore, it can expose

field personnel to risks such as potential threats from unpaid suppliers or growing frustration from communities due to delays.

While humanitarian financial transactions are safeguarded, the process of identifying suitable banks, establishing trust, and overcoming their internal restrictions requires time-consuming strategies.

The following protocol, extracted from an organisation’s actual standard procedure, is typically sustained until multiple reliable banking pathways to a target intervention area are secured:

Pathways pre-identification: The end destination bank should pre-identify intermediary banks capable of facilitating transfers to the sanctioned area.

Creation of a detailed brief:

- Presenting the organisation and its humanitarian purpose per its charter.

- Outlining the specific humanitarian intervention in the sanctioned area.

- Highlighting the funding sources allocated to the projects.

- Clarifying the transaction purposes (e.g., salary payments, instalments to supplier).

Engagement with the originating bank: Scheduling face-to-face sessions with the bank's compliance or non-profit-focused department to build a direct, trusting relationship.

Maintaining an open dialogue with the originating bank regarding current/ anticipated transfers.

Banking pathway final assessment: Mapping out financial entities based on their cooperation level, differentiating between those that are receptive and those that exhibit more resistance.

After concerted awareness campaigns by US-based NGOs on the overcompliance of banks regarding transfers to Syria, OFAC responded with FAQ 984,4 on November 8, 2021, offering clarifications:

- US financial institutions are now advised to facilitate funds transfers to sanctioned jurisdictions upon the provision a copy of a grant or contract from the Federal Government

- Non-U.S. entities, which encompass NGOs, private sector firms, and financial institutions engaged in facilitating or aiding these activities, are explicitly exempt from the risk of U.S. secondary sanctions

pursuant to the Caesar

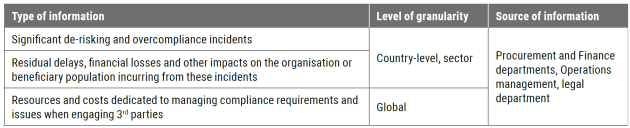

Why do we collect this information?

To address de-risking and overcompliance issues, it is crucial to demonstrate the impact that each significant incident has had or may have had on the organisation. Experience has shown that without robust, evidence-based data, any narratives aimed at influencing relevant decision-makers regarding this specific topic might be dismissed as mere conjecture. Concrete evidence such as average delays, financial losses, or instances of operational discontinuity cases serve as hard proofs.

This issue highlights a significant challenge: the task of persuading a broad spectrum of decision-makers (cf chart of typical stakeholders above).

Departments impacted by overcompliance from a supplier or bank typically engage with its commercial division, which possesses limited influence on risk management decisions. This highlights the need to establish with their legal departments. On the governmental level, organisations usually interact with Foreign Affairs (MoFA) representatives, even

though regulations shaping third-party obligations are overseen by supervisory ministries and administrations such as Budget, Finance, and Economy. Data collection serves two key purposes here: (i) presenting fact-based arguments to

stakeholders with differing perspectives and (ii) strengthening the advocacy efforts of our allies (e.g third party commercial services and MoFA) in discussions with their more cautious counterparts.

How can it be operationally useful?

Overcompliance cases have their most salient impact on specific global support departments, most notably finance and procurement. Collecting systematic evidence of de-risking practices empowers these departments to precisely identify bottlenecks, opening the door to several mitigation solutions:

- Addressing them more effectively through targeted bilateral engagement with banks and lobbying initiatives with involved third parties. e.g: by pinpointing problematic transactions, along with their background history, the procurement department of an organisation may be able to mobilise its legal division in more proactive ways and together establish strategies for addressing suppliers who apply over-compliance measures.

- Isolating the problematic links in a chain of issues and circumvent them through alternative options. e.g: A finance department, for instance, can examine its year-long register of bank transfer issues to unveil patterns of problematic routings. This analysis might reveal two intermediary banks responsible for 30% of these issues. Armed with this

knowledge, the finance department can effectively negotiate alternative routings with their primary banks, thereby circumventing the problematic links in the chain.

Tool E: Overcompliance incidents in International Procurement

Type: Register

Tool F: Overcompliance incidents in International Bank Transfers

Type: Register

Tool G: SCTM Organisational impact

Type: Survey

Tabs: Finance, Procurement

Tool J: Country Risks and Impact

Tool type: Survey

Tabs: Finance, Procurement

Local security and counterterrorism measures

Local security and counter-terrorism measures refer here to a collection of laws, decrees, and administrative actions

within a given country where humanitarian operations occur. The primary purpose of these measures is to empower national or local authorities to counteract armed groups. Their objectives may include disrupting funding channels, restricting movement, or reducing potential support. The distinction between counter-terrorism objectives and broader security rationale can be nebulous, often hinging on the political narrative underpinning their enactment.

Some of these measures are derived directly from international sanctions and translated into the country’s domestic normative framework. Others are autonomous measures - for instance targeting entities considered as local terrorists but

not listed on the UN designation lists, or implementing safety provisions with no equivalent in the international legal framework. These autonomous measures generally create a more complex legal and administrative landscape for humanitarian actors to navigate.

Form and ownership

These measures can manifest in various forms, such as national laws present in criminal, monetary, or financial codes, or in the shape of executive orders such as decrees, edicts, or ministerial circulars. Dependently, they can originate from:

- National authorities: Passed through parliamentary processes or introduced by various ministries.

- Regional entities: Such as governors or local parliaments.

- Military representatives: Depending on the conflict dynamics and the authority vested in the military.

Scope

Some local security and counter-terrorism measures may specifically target the humanitarian sector:

- By restricting standard operational practices such as the exchange of information regarding humanitarian and security situations.

- By prohibiting dialogue and engagement between humanitarian entities and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) labeled as terrorist organisations. On other occasions, while not directly targeting humanitarian interventions, restrictive measures can inadvertently affect operations or particular vulnerable groups supported by the humanitarian

or development sectors. This is often the case with blanket restrictions that restrict movement to or within specific areas or limit the import and use of sensitive materials (e.g: dual-use material), which are crucial for both humanitarian actions and the well-being of supported populations.

Interpretation

In many contexts of intervention, the enforcement of these measures often hinges on their interpretation by local or overseeing authorities. For instance, a provincial governor might interpret a presidential decree calling for enhanced traffic monitoring in volatile zones as an outright ban on motorcycles and lorries. Occasionally, these initial directives are only conveyed verbally, further complicating their understanding and appropriate enforcement by relevant stakeholders.

Understanding both the application and consequences of local security and CT measures can be daunting. Country Teams might lack the resources or bandwidth to proactively monitor every new regulation and its localised application.

A more pragmatic approach to analysis could be centered around monitoring issues. This integrates seamlessly into existing processes, such as the tracking of security incidents, offering the opportunity to assess their connection to security and counter-terrorism measures.

Several types of issues may arise from these measures, impacting both international and local NGOs:

- Access incidents refer to various impediments that hinder the prompt delivery of humanitarian aid to areas deemed sensitive, such as disputed regions or places with a presence of non-State Armed Groups. They can also involve barriers preventing populations in need from receiving assistance. E.g.: To streamline local police inspection efforts, the governor of "area X" implements alternate-day traffic regulations in the region's primary cities. This reduces daily vehicle flow, thereby impeding the organisation's ability to manage daily aid distributions in at-risk communities.

- Criminalisation pertains to any incident where there is a risk of legal action or executive directives against the organisation and its affiliates. This can for instance manifest as temporary detainments. E.g.: a military commander dispatches two officers to caution the organisation's Field Coordinator assistant about the potential detention of personnel if vaccination efforts on a specific camp's periphery continue without prior military review of the recipients.

- Reputational damages arise from adverse local perceptions about the organisation's purpose, activities, or stance, particularly on matters of national security or integrity. Such risks can foster local scepticism towards the organisation or the broader aid community, evidenced by public condemnations, criticism from political leaders, or growing mistrust from local administrations. E.g.: after recent attacks by an opposition group in the capital, the government issues stringent counter-terrorism directives targeting the group and its origin region. With organisation

"Y" working in that region and having coordinated with the group for five years, its team now faces public confrontations from angry locals in the capital city. - Security incidents frequently arise from diminished approval of the organisation and its activities by military entities. This might be due to perceptions of the organisation's alignment with what's viewed as a terrorist agenda (leading to reduced acceptance by official forces) or, conversely, perceived compliance with anti-terrorist views (resulting in reduced acceptance by non-State armed groups). After the government implements stringent counter-terrorism measures, the organisation continues delivering medical supplies in Region Z, unnerving official armed forces. However, by denying a local non-State armed group exclusive supplies, they are perceived as aligning with the new measures.

Why do we collect this information?

Local security and counterterrorism measures can impede humanitarian efforts by restricting engagement, negotiation, program execution, and partner capabilities. It has the potential to undermine certain response goals and objectives. Collecting quantitative data on the frequency of issues, as well as qualitative insights into their causes and ultimate effects, can serve various advocacy purposes:

- Establishing a stronger foundation for advocating locally against the misuse or unintended consequences

of security and counter-terrorism measures. - Identifying factors that initiate, worsen, or mitigate issues. This information can be instrumental in

adopting proactive measures, such as educating local authorities or conducting joint risk analyses. - Highlighting the ripple effects of a global counter-terrorism climate on the security practices of conflictaffected

States, especially in aid-recipient countries.

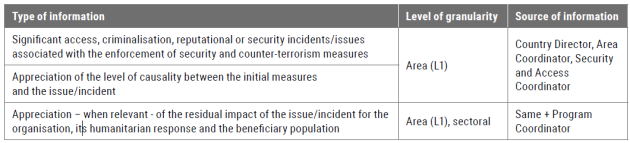

What information do we want to collect?

How can it be useful to operations?

Beyond advocacy purposes, analysing the impact of national or local security and counter-terrorism measures on humanitarian operations or specific sectors at risk can yield several benefits:

- Supporting the different phases of the programming cycle, by offering additional data about the extent of impact these measures have on operations and on specific categories of populations and communities.

- Improving the knowledge of legislative or executive measures that may represent a risk for the organisation, thereby helping to formulate appropriate mitigation measures.

- Helping maximise and adapt negotiations with national or local authorities as well as regulatory bodies

- Facilitating engagement with coordination mechanisms and donors in addressing the impediments caused by these measures.

Tool H: Local Security and CT regulations

Type: Register

Tool I: Incidents related to Local Security and Counter-Terrorism Measures

Type: Register

Tool J: Country Risks and Impact

Type: Survey

Tab: Access

The data collection tool was developed and designed by Action Against Hunger, Médecins du Monde, and Humanity & Inclusion.