Humanitarian Access Working Group Toolkit

1: Understanding

The guiding frameworks, concepts and principles underpin humanitarian access and form the basis of nearly every activity a humanitarian access working group (HAWG) might engage in. It is vital that not only an HAWG’s leadership but also its members understand them to help foster informed and impactful coordination.

Building this understanding is particularly important if an HAWG’s leadership and/or members are less experienced or new to the sector.

There is a wealth of existing information and research on the topics highlighted below. We have selected some of the most relevant for humanitarian access practitioners, which can be found here.

Humanitarian access

Humanitarian access is generally defined as humanitarians’ ability to reach affected populations and plan, implement, deliver and monitor aid interventions in a principled way; and people’s ability to access assistance and protection safely and in dignity.

As a concept, it is most frequently associated with areas experiencing armed conflict, disasters and/or other emergencies.

It is a fundamental part of humanitarian action. Without some degree of access, it would be impossible to provide assistance.

It is important to remember that humanitarian access is a dual concept. More focus is often given to humanitarians’ access compared to people’s access. One way to offset this potential imbalance is to ensure HAWGs work closely alongside protection clusters, including having them as members.

Given the breadth of issues that fall under both sides of humanitarian access, it is understandable that an HAWG will prioritise some over others, but it should do so consciously. If people’s access is not to be given equal attention, then such a decision should be part of a clearly communicated prioritisation process. Ultimately though, the HCT is likely to set an HAWG’s access priorities and tasks.

Access constraints

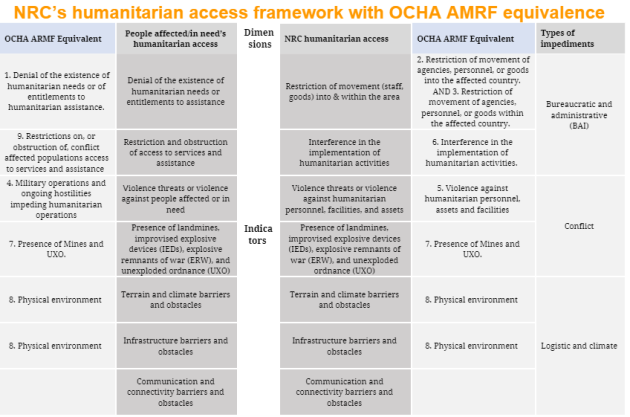

Humanitarian access is rarely unfettered. A number of issues regularly hinder it on both sides of the equation. The United Nations (UN), non -governmental organisations (NGOs) and others have defined these barriers in largely similar ways, with some nuances across categories. Those in the chart below are generally seen as the standard access barriers as defined by OCHA and NRC.

*AMRF = OCHA’s access, monitoring and reporting framework

Discussions about humanitarian access constraints often include descriptions of areas deemed hard-to-reach (H2R) or inaccessible.

NRC defines H2R as affected population groups and areas inhabited by people in need that are unable to receive humanitarian services covering their basic needs because of a significant and sustained denial of access, the continual need to secure access or other restrictions.

Access coordination

Every humanitarian organisation will pursue their own strategies and approaches to secure and sustain access. Coordination refers to the collective efforts of various stakeholders to facilitate it. These efforts are most often undertaken in settings such as humanitarian country teams (HCTs), HAWGs, civil-military coordination (CMCoord) cells, NGO forums and sometimes sectoral clusters.

There are various ways access coordination forums can help to address constraints, including:

- Gathering information and providing analysis to inform common decision making

- Developing response-level access strategies and operating principles

- Developing talking points to support private advocacy and public communications

- Adapting the ways humanitarian assistance is provided

- Advising decision makers on when assistance should be limited, suspended, or withdrawn

There are good reasons to pursue collective efforts. They strengthen humanitarians’ position in negotiations and advocacy by presenting a united front, reducing the likelihood of humanitarians taking contradictory or harmful approaches and protecting individual organisations from potential retaliatory action by an assertive actor.

Humanitarian access is based on two foundational pillars: the humanitarian principles and the international normative framework.

Humanitarian principles

Humanitarian principles provide the fundamental foundations for humanitarian action and are the central feature of humanitarians’ identity. They are central to establishing and maintaining access to affected people in any setting.

The principles of humanity, neutrality and impartiality are endorsed in UN General Assembly resolution 46/182, which was adopted in 1991. The principle of independence was added in 2004 under resolution 58/114.

What are the principles?

This is the primary rationale and defining characteristic of humanitarian action. From an access practitioner’s perspective it includes making efforts to negotiate access to, and presence in, areas where needs are highest, and a commitment to engage with affected communities. The principle of humanity is the overriding guiding principle of our work.

Humanitarian aid should be based on need only, regardless of who the people we serve are or where they are.

Being neutral should not limit humanitarians from engaging with all actors to ensure aid reaches people in need, including NSAGs, de-facto authorities and criminal groups. Access practitioners play a key role in ensuring this mandate is fulfilled.

Many humanitarians will often not be entirely independent. They might rely on the UN Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) for means of transport to H2R locations or have their operations dictated by a small number of western donors. An access practitioner should always be mindful of when any such loss in independence starts to affect the other humanitarian principles.

Why do the humanitarian principles matter?

Adherence to the principles is a key enabler for humanitarians to be able to access people in need. In ideal circumstances, a warring party, local authority or community will know that a humanitarian organisation is neutral, that its only objective is to assist and protect people in need, and that it is not interested in taking sides in a conflict or favouring one group of people over another.

The reality is frequently more complicated. External stakeholders often perceive humanitarians as not adhering to the principles, which can lead to the imposition of access constraints. Humanitarians’ criticism of an armed actor for targeting civilians is a typical example of being seen to take sides in a conflict. It is important to carefully weigh whether the risks of public advocacy outweigh the benefits and potentially further limit access. Other forms of engagement and diplomacy are preferable at the initial stages.

Access in international humanitarian law

Humanitarians frequently refer to international humanitarian law (IHL) in discussions about access because it speaks to the rights and obligations of parties to a conflict as well as humanitarians in times of armed conflict.

IHL applies in two situations: international armed conflict (IAC), which takes place between states, such as the current war between Ukraine and Russia; and non-international armed conflict (NIAC), in which at least one non-state group is involved, such as the conflict between the United States-led coalition in Iraq and Syria and the Islamic State group. Different IHL conventions apply depending on how a conflict is categorised.

The most basic rules of IHL revolve around prohibiting attacks on civilians and civilian objects, ensuring that civilians and combatants who are not fighting anymore are protected, and that certain categories of people - such as children, medical personnel, humanitarians, women, displaced people and those with disabilities - receive additional protection.

National legal frameworks, traditional or customary norms and religious norms also provide foundations for access and can often be more impactful in helping frame engagement with actors for whom international laws are of lesser importance.