Toolkit for principled humanitarian action

5. Sanctions, counterterrorism and risk management frameworks

This section explores practical aspects of risk management and steps your organisation can take to strengthen risk management policies and practices, while maintaining a principled approach. It endeavours to make risk management approaches accessible and understandable to a broad range of staff, including those who are field-based and responsible for programme implementation.

What is risk management?

Risk management is a process to help staff systematically think though what risks may arise in specific contexts and what can be done to mitigate these. It addresses the question of what organisations can do to make sure that as those most in need are assisted as much as possible in a principled manner, despite challenging contexts, by identifying, monitoring and tackling key risk factors.

Definitions:

- Risk: Uncertainty, whether positive or negative, that may affect the outcome of an activity or the achievement of an objective.

- Risk management: a cycle of identifying and assessing risks, assigning ownership of them, taking action to anticipate and mitigate them, and monitoring and reporting progress.

Why use a risk management framework?

Owing to the nature of the environments they work in, staff of humanitarian organisations constantly manage risk. Where this is done in an ad-hoc manner there may be gaps and inconsistencies in the way risks are identified and managed. In order to prevent this, organisations should consider adopting a framework to establish clear processes for identifying and managing risks. Sanctions and counterterrorism issues should feature strongly within this framework. The key components of a risk management framework are outlined in this section. Where an organisation does not have a clear risk management approach in place staff and teams can still apply these risk management processes to the contexts they work in to address possible sanctions and counterterrorism issues.

| Risk | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Operational | → | Inability to achieve objectives |

| Security | → | Violence or crime |

| Safety | → | Accident or illness |

| Fiduciary | → | Misuse of resources, including fraud, bribery and theft |

| Information | → | Data loss, breaches or misuse |

| Legal/compliance | → | Violation of laws and regulations |

| Reputational | → | Damage to integrity or credibility |

| Operational | → | Inability to achieve objectives |

| Ethical | → | Insufficient application of the humanitarian principles and duty of care, lack of adherence to organisational values and mandate |

Components of a risk management framework

Risk management has four main components:

- Identification

- Assessment

- Monitoring

- Reporting

1.Identification

Risks can be grouped into two main categories, external and internal, and many subcategories. A SWOT analysis can used to identify risks, with strengths and weaknesses focusing on internal sources of risk and opportunities and threats focusing on external ones.

Organisations should try to identify all risks, including those associated with sanctions and counterterrorism measures. Once identified, these should be added to an internal risk register, which should be reviewed and updated regularly to account for any changes in context or environment.

2. Assessment

Once an organisation has identified and classified its risks in a register, it needs to assess them. This tends to be done by assigning each risk a numerical value, often on a scale of one to five, for its likelihood, impact and sometimes an organisation’s vulnerability to it. The values are then combined to establish an overall score for each risk.

There are various ways of assessing risks objectively. The table in Tool 10: Criteria for calculating risk shows some criteria for evaluating risk impact and likelihood values. The overall scores for each risk can then be put into Tool 11: Risk matrix to create a concise visualisation of the risk assessment.

Establishing a score for residual risk allows an organisation to assess whether the risks are outweighed by the expected humanitarian outcomes of the activity involved. This assessment can be made using programme criticality tools, such as this one used by the UN. The outcome of this assessment can vary depending on an organisation’s risk appetite, or willingness to accept risk, and its risk tolerance, or capacity to accept risk.

Once an organisation has identified and put risk mitigation measures into place for a particular risk—for example, sanctions and counterterrorism measures—it must then assess whether there are any associated residual risks that it is unable to mitigate. After identifying these residual risks, the organisation must then assess them against its own risk appetite, or willingness to accept risk. One way to assess whether a particular risk might be outweighed by the importance of the activity involved is through a programme criticality framework.

A programme criticality framework is an approach to inform decision making around an organisation’s level of acceptable risk, particularly risks that remain after an organisation has put risk mitigation measures into place. It can provide a structured process to decision making that evaluates the balance of implementing an activity against the residual risks faced. A programme criticality framework should use a set of guiding principles and a systematic, structured approach to decision making to ensure that activities involving an organisation’s personnel, assets, reputation, security, etc., can be balanced against various risks. Programme criticality frameworks can also help an organisation weigh residual risks against commitments to humanitarian principles, particularly those guiding who the organisation assists, and the principles of humanity and impartiality.

In the current context, many donors are pushing implementing organisations to programme in very difficult areas while also maintaining a no-risk expectation. In most of the humanitarian contexts where humanitarian organisations operate today, these two expectations are increasingly at odds and have forced practitioners to try and develop more systematic approaches to navigating these dilemmas. If an organisation has already implemented all the risk mitigation measures it deems feasible, but it is left with residual sanctions and counterterrorism risks, the next step could be for the organisation to develop a programme criticality framework.

3. Monitoring

Approaches to monitoring risk vary, but organisations tend to do so every quarter or trimester. They may also carry out ad-hoc monitoring if a specific trigger occurs. Risks related to specific programmes should be monitored throughout the programme cycle and discussed at programme review meetings.

4. Reporting

Reporting on risk management should form part of the wider reporting processes that cover an organisation’s overall direction, effectiveness, supervision and accountability.

- Direction: providing leadership, setting strategy and establishing clarity about what an organisation aims to achieve and how

- Effectiveness: making good use of financial and other resources to achieve the desired humanitarian outcomes

- Supervision: establishing and overseeing controls and risk management and monitoring performance to ensure an organisation is achieving its goals, adjusting where necessary and learning from mistakes

- Accountability: reporting to on what the organisation is doing and how, including reporting to donors

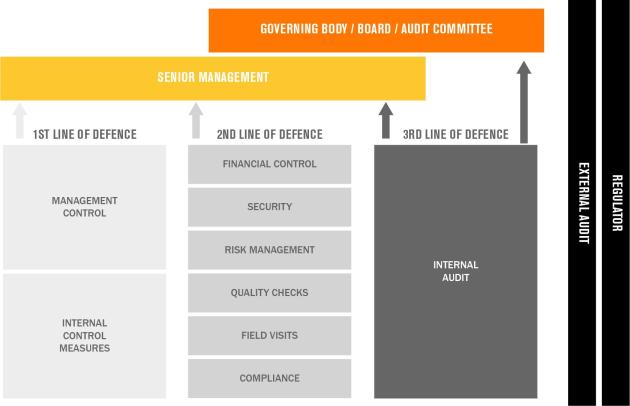

The “three lines of defence” model is an example of a governance model of which risk management is a key component.

Management control and internal control measures make up the first line of defence; the various risk control and oversight functions established by management make up the second; and independent assurance makes up the third. Each of the three lines of defence plays a distinct role in an organisation’s wider governance framework.

An example application of this model could relate to a specific sanctions or counterterrorism measure, such as the screening of suppliers or employees, that would be implemented by staff in field offices. The process would require oversight from management as the first line of defence. As a second line of defence, compliance staff at the country or regional level would conduct spot checks and review implementation. The third line of defence is the organisation’s internal audit team, which provides overall assurance to global management on the effectiveness of internal control procedures through regular audits.

The US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), part of the US Treasury Department, is primarily responsible for the implementation and supervision of the US sanctions programmes. Its Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments strongly encourages organisations bound by sanctions regimes “to employ a risk-based approach to sanctions compliance by developing, implementing and routinely updating a sanctions compliance program (SCP)”. The existence and effectiveness of such a programme is identified as a factor in any enforcement proceedings OFAC takes against organisations that may have violated sanctions and can reduce the amount of any fine imposed.

OFAC states that an effective SCP should have five elements, all of which overlap considerably with the components of a risk management framework:

- Management commitment: Senior management should give compliance functions sufficient resources, authority and autonomy to manage sanctions risks and promote a culture of compliance in which the seriousness of sanctions breaches is recognised.

- Risk assessment: Organisations should conduct frequent risk assessments in relation to sanctions, particularly as part of due diligence processes related to third parties, and develop a methodology to identify, analyse and address the risks they face.

- Internal controls: Organisations should have clear written policies and procedures in relation to counterterrorism-related compliance, which adequately address identified risks, and which are communicated to all staff and enforced through internal and external audits.

- Testing and auditing: Organisations should regularly test internal control procedures to ensure they are effective and identify weaknesses or deficiencies that need to be addressed.

- Training: There should be a training programme for employees and other stakeholders, such as partners and suppliers.

The UK’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI), within the UK Treasury Department, performs a similar role. OFSI advises organisations to UK charities and similar organisations to implement a strong sanctions compliance programme proportionate to the risks faced. This should include:

- “communicating compliance expectations with partners, subsidiaries, and affiliates in line with local regulations

- developing, implementing, and adhering to written, standardised operational compliance policies, procedures, standards of conduct, and safeguards

- implementing compliance programmes, which should specify that engagement in sanctionable conduct may result in immediate termination of business or employment, or alternatively, confirm the adoption of controls to mitigate associated risks

- protecting employees that disclose illicit behaviour from retaliation and establish a confidential mechanism for reporting suspected, actual illicit or sanctionable activity

OFSI’s compliance and enforcement model has four elements:

- Promote compliance by publicising financial sanctions.

- Enable compliance by providing guidance and alerts to organisations to help them fulfil compliance responsibilities effectively.

- Respond to non-compliance consistently, proportionately, transparently and effectively.

- Change organisations’ behaviour through compliance and enforcement action, which will take account of measures being taken to improve future compliance.

Internal controls and risk management

Internal controls are key elements of risk management frameworks. They include processes to assess, mitigate and monitor risks. Organisations can embed internal controls throughout the programme cycle and as part of its overall governance structures and reporting systems.

Internal control systems can be characterised as follows:

- Preventive: measures such as anti-diversion policies to ensure aid reaches its intended beneficiaries.

- Corrective: measures such as internal checks to establish whether sanctions and counterterrorism-related risks have arisen during the programme cycle.

- Directive: measures such as sanctions and counterterrorism policies that give staff clear guidance and establish red lines in relation to sanctions and counterterrorism risks.

- Detective: monitoring measures such as spot checks to review whether staff have complied with sanctions and counterterrorism requirements.

The following section examines various internal controls and approaches to the management of risks associated with sanctions and counterterrorism measures. It includes the following components:

- Sanctions and counterterrorism policies

- Policies for engagement with NSAG

- Due diligence

- Human resource policies

- Anti-diversion policies

- Monitoring and evaluation

Developing a sanctions and counterterrorism policy

Sanctions and counterterrorism policies are intended to ensure that staff comply with relevant sanctions and counterterrorism measures while maintaining adherence to the humanitarian principles. They can articulate an organisation’s mandate, and reiterate its commitment to the humanitarian principles, IHL and other laws and measures. They may include an overview of the measures the organisation has put in place to address concerns about the diversion of humanitarian assistance, including to persons and entities designated under sanctions or groups proscribed under counterterrorism measures. See Tool 12: Example sanctions and counterterrorism policy .

- A member of senior management should be the focal point for managing this undertaking

- Departments at headquarters and the field level should be tasked with providing inputs to the draft policy and reviewing it

- Inputs from a legal adviser should be sought

- The principles and mandate to which the organisation is committed

- An overview of the laws that bind the organisation, which may include IHL, domestic laws in the countries where it is registered and operates, sanctions laws and counterterrorism measures

- The principles and commitments of staff members, such as ethical behaviour and anti-diversion

- An overview of the measures the organisation has in place to provide principled humanitarian assistance, such as robust project cycle management (PCM), codes of conduct with oversight mechanisms, anti-corruption procedures, financial and procurement controls and procedures for the selection of partners and staff

- A statement of red lines that if crossed would constitute a breach of the policy

- The policy should be developed in a consultative, collaborative process to ensure it addresses the main issues that staff confront and guarantees buy in and acceptance among staff members

- A robust roll-out plan should be established, which includes awareness raising and staff training on how to adhere to the policy

- Staff should be provided with written guidance on the policy in an accompanying explanatory note that gives further detail of due diligence procedures, relevant handbooks and SOPs

- Focal points to whom staff can turn with questions or to seek advice when dilemmas arise should be identified

- Control and oversight mechanisms, such as a reporting mechanism for violation of the policy, should be developed

- Authoritative statements of principles and ethics, signed and endorsed by senior management, should generally not be revised

- Other policy elements may need to be revised as sanctions and counterterrorism measures evolve and their impact on principled humanitarian action changes

Developing an NSAG engagement policy

NSAGs are present in most contemporary armed conflicts. In some contexts, NSAGs are designated for the purpose of sanctions by the UN, the EU or by host or donor states, or proscribed under criminal counterterrorism measures. Humanitarian organisations may engage with NSAGs, regardless of whether they are designated or proscribed, for various purposes, including to negotiate access to populations in need of assistance.

To manage risks related to engagement with NSAGs who may be designated or proscribed, some humanitarian organisations have developed policies for NSAG engagement that consider sanctions and counterterrorism measures. These policies can help avoid the transfer of risk onto field-based staff by ensuring that staff have clear organisational guidance and support when engaging with these groups.

NSAG engagement polices should consider three sources of sanctions and counterterrorism measures: sanctions adopted by the organisation’s state of registration and the host state, counterterrorism measures adopted by these states; and any sanctions and counterterrorism clauses in grant agreements. See Tool 8.

This content was developed in collaboration with Geneva Call. Geneva Call is a humanitarian organization working to improve the protection of civilians in armed conflict. Geneva Call engages NSAGs to encourage them to comply with the rules of war. More information about the organisation’s work can be found here.

Developing an NSAG engagement policy that considers sanctions and counterterrorism issues

- What is the purpose of the organisation’s engagement with NSAGs? For example, an organisation that delivers humanitarian assistance may be concerned about indirect terrorist financing or violation of sanctions regimes, while an organisation working to promote IHL may be more concerned about broad prohibitions in material support laws.

- How does the organisation safeguard the humanitarian principles in its engagement with NSAGs? How might the principles be challenged during engagement with NSAGs? For example, is there a risk to the organisation’s independence through potential interference in beneficiary selection?

- What are the red lines in the engagement? Under what conditions would the organisation consider discontinuing engagement?

- What are the possible reputational risks for the organisation engaging with NSAGs? How can these risks be mitigated and managed?

- Do internal policies and procedures account for risks to staff emanating from national and international legislation? What are the potential consequences if the organisation engages with an NSAG that is designated under a sanctions programme or proscribed as terrorist by the host government, on both its operations and its staff? What are the consequences if the organisation does not engage?

- Does the organisation track which staff members are negotiating with NSAGs? How does the organisation document negotiations processes? How is relevant data and information stored and protected?

- Do the organisation’s grant agreements include clauses that prohibit using funds for NSAG engagement for general or specific purposes? Do relevant donors require due diligence steps during such engagement? If necessary, clarification or guidance should be sought internally. Refer to Tool 8 more guidance on reviewing such clauses in grant agreements.

- Is the NSAG designated under UN or EU sanctions or by individual states, such as the US or by the host state? Are high profile members or leaders of the NSAG designated under any of these regimes? It must also be whether the group or its members are designated under sanctions regimes that are not necessarily counterterrorism-related, as regardless of their objectives, sanctions can impact the broader legal and policy environment for a humanitarian organisation’s engagement.

- If the answer to any of the above questions is yes:

- What is the scope of the sanctions/counterterrorism measures and how may they impact the organisation’s operations? Sanction regimes do not prohibit contact with designated persons or entities, but financial sanctions may require that organisations ensure that funds or assets are not made available to these groups.

- Are there any safeguards in the sanction regime or is there a possibility to apply for a license? Exemptions normally require approval by the authority in charge of implementing the sanctions.

- What are the consequences for violating sanctions regimes for the organisation and for staff members?

- If staff members have questions about relevant sanctions regimes, who should they approach internally for support and guidance?

- Is the NSAG proscribed under the counterterrorism measures of states, such as the US or by the host state.

- Has the organisation identified and mapped how the organisation and staff could be impacted by criminal counterterrorism measures? Local staff members may be particularly exposed to risks related to host-country counterterrorism measures. The following elements should be considered in such a mapping:

- The national legislation of the host state, the state of registration of the organisation, the states of nationality of staff, donor states and third states with broad extraterritorial offences.

- The jurisdictional links required. For example, is there a requirement for a link of nationality of staff, or of registration of the organisation?

- The typical offences that could lead to the potential criminal responsibility of staff, include the following: prohibition of indirect financing of terrorism, material support laws, designated area offences that prohibit presence in areas of designated terrorist activity and the prohibition of broad forms of association with proscribed groups.

Due diligence

Due diligence encompasses a range of activities undertaken to ensure that humanitarian assistance reaches affected populations. When entering into an agreement or contract with another party, such as an implementing partner, due diligence includes assessing the robustness of its systems and its ability to carry out the relevant activities within the limits of an organisation’s acceptable level of risk.

Due diligence can involve both internal and external-facing policies and measures designed to obtain assurance of a potential partner’s capacity and capability to deliver assistance and to comply with donor requirements, including those related to sanctions and counterterrorism. Reviewing a potential partner’s policies, systems, processes and past performance can lead to a more informed partnership that identifies, accounts for, and takes the appropriate measures to mitigate risks. Tool 14: Partnership assessment checklist could help guide an organisation’s decision on whether to pursue a potential partnership.

Conducting due diligence with prospective partners

- Explore opportunities for working together and identify areas for cooperation in the delivery humanitarian programs

- Ensure a possible partner organisation has effective systems and operational procedures in place

- Understand the acceptability and reputation of partner with communities and local authorities

- Assess whether a potential partner poses a financial, reputational or programmatic risk to an organisation’s operations and/or a protection risk for beneficiaries

- Confirm that the partner is not listed in any excluded party list due to linkages with criminal or political activity, terrorism or diversion of funds

- Confirm that the partner has the internal capacity to comply with all clauses influencing and included in any possible agreement, including those related to sanctions and counterterrorism

- Areas covered in a due diligence assessment will vary based on the specific situation, needs and context. Some of the domains to consider reviewing in a partnership due diligence assessment include:

- Basic background and history

- Mission and values

- Governance

- External engagement, influence, and reputation

- Organisational capacity

- Operational capacity

- Financial capacity

- Logistical capacity

- Human resources policies and codes of conduct

- Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA), criminal, and unethical activity policies

- Corruption and conflict of interest policies

- Sanctions and counterterrorism policies and procedures

- Stated commitments to the humanitarian principles and a do-no-harm approach

- Organisations can conduct due diligence assessments with the prospective partner by collecting information directly

- Organisations can collect information from other sources (e.g. other organisations that work with the prospective partner)

- Organisations can request a prospective partner complete a self-assessment; this should be used in tandem with the organisation’s own due diligence assessment

Humanitarian organisations should ensure they institute human resources policies, including transparent and fair recruitment protocols, and communicate these clearly to staff. Human resources policies are a key part of organisation-wide risk management approaches and, as such, can help mitigate sanctions and counterterrorism-related risks and reassure donors. Human resources policies include rules for recruiting, training, appraising, remunerating, disciplining and dismissing staff. Humanitarian organisations frequently include them in staff contracts as a legally binding set of obligations that both parties are expected to observe.

Codes of conduct are another important element of human resources policies. Codes of conduct establish standards of behaviour for an organisation and its staff. They commonly reflect a commitment to the humanitarian principles, mitigating the likelihood of compromising them.

Codes of conduct are non-binding, but they are often included in staff contracts, in which case they become a set of obligations that must be observed. Some organisations provide training and written guidance to staff on how to put their codes of conduct into practice. Codes of conduct may also include control and oversight mechanisms, such as disciplinary proceedings and whistle-blowing facilities.

Reviewing and developing human resources policies

- Recruitment: Does the human resources policy and the recruitment procedures it governs ensure the most suitable and best-qualified candidates are selected, having undergone reference and employment verification and other checks?

- Staff development: Does the human resources policy stipulate a plan to develop staff members’ skills and improve the knowledge they require to do their job and progress in the organisation?

- Discipline: Does the policy establish clear procedures and rules for censuring staff members who violate the organisation’s rules and regulations?

- Appraisals: Does the policy detail how and how often such assessments take place?

- Duty of care: what steps does the organisation take to ensure the health, safety and wellbeing of staff.

- Senior management, in consultation with the human resources department, is responsible for developing, reviewing and ensuring implementation of human resources policies.

- The legal department should also be consulted during their development.

- How to recruit, dismiss, remunerate, train and appraise staff

- How to develop a staff member’s skills for their role

- How to discipline staff members for violations of the organisation’s policies

- Human resources policies should be clearly communicated to all staff

- Relevant training should be available to staff

- A confidential complaints or feedback mechanism should be put in place

- There is no set schedule for doing so, but many organisations revise their human resources policies periodically or during a change in the organisation’s circumstances

Anti-diversion policies

Humanitarian organisations have anti-diversion policies to mitigate the likelihood of assistance being diverted from affected populations. They may include:

- Measures to limit the likelihood of fraud and corruption

- Procedures to regulate financial management

- Guidance on access negotiations

- Measures to reinforce an organisation’s policies in areas such as training, information sharing, disciplinary investigations and monitoring

Reviewing and developing anti-diversion policies and practices

- There are no standardised anti-diversion policies, but they tend to address:

- Embezzlement: The misappropriation of goods or funds for financial or personal gain

- Fraud: Deception, for example by falsifying records to exaggerate the number of staff employed or beneficiaries covered by a project, to result in financial or personal gain

- Corruption: Dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, typically involving bribery; the aim of anti-corruption policies, including those on whistleblowers, is to ensure staff act ethically

- Money laundering: The concealment of the origin of money obtained from criminal, terrorist or other illegal activities

- Access: The methods by which an organisation engages with armed groups and negotiates humanitarian access

- Overall responsibility lies with senior management, which should assign responsibility to the relevant departments for implementing practices related to staff training, producing written guidance and carrying out control mechanisms such as audits

- Field staff have a key role to play in the development of anti-diversion policies and practices, and should be consulted to ensure they are relevant and realistic

- The legal department should also be consulted

- A statement of principles and definition of terms

- Procedures for preventing diversion: standardising and maintaining bank records; standardising accounting practices, such as account codes and donor codes; classifying costs, for example as direct or indirect; ensuring internal controls, including the segregation of duties between staff responsible for procurement, finance, disbursing cash, payroll and liquidations; and financial reporting requirements

- All staff should receive training on the organisation’s anti-diversion policies

- All staff should receive written guidance on implementation

- Control and oversight mechanisms, such as audits, spot checks and regular reports, should be put into place

- There is no set schedule for doing so, but many organisations revise their anti-diversion policies every few years or if they are found to no longer be fit for purpose

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks

Counterterrorism and M&E

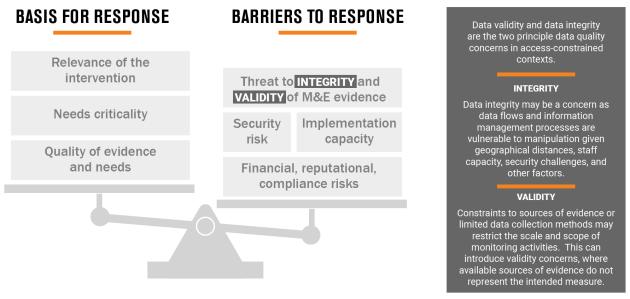

M&E serves two purposes for humanitarian organisations. It provides the basis for learning and programme improvement, and it establishes evidence to meet internal and donor-related documentation and reporting requirements.

Humanitarian organisations should pursue three M&E strategies to mitigate sanctions and counterterrorism related risks:

- Implement the best M&E system possible in the given context

- Ensure transparency regarding the quality of M&E feasible

- Take considered programme criticality decisions where M&E evidence is absent or weak

Sanctions and counterterrorism risks often arise in situations where humanitarian access is already constrained because of the presence of armed groups that can be sanctioned or proscribed. In situations of constrained access M&E processes may be imperfect and there is a risk that some data may not accurate. An accurate assessment of the quality of M&E processes helps to determine how successful an organisation has been in using them to mitigate the risk that resources are diverted to DTGs.

A tool such as Tool 15: M&E minimum standards can help measure the quality of M&E processes objectively. The minimum standards also provide a concrete way of communicating M&E risks to donors to ensure that all parties are aware of them before a project is implemented.

M&E quality is an important consideration during programme criticality decision making. If the M&E minimum standards in Tool 10 indicate that M&E processes will be weak, management should take a programme criticality decision to weigh the potential humanitarian results of the intervention against the associated obstacles and risks, in this case to decide whether it is worth implementing the project if little or no data on its outcomes will be available.

Developing and implementing M&E systems

- Results framework: This is a cause-and-effect explanation of a project that predicts how activities and inputs will contribute to the objectives of the intervention. It should include indicators the project will measure to test key assumptions.

- Indicator matrix and monitoring tools: The former defines each indicator and stipulates how and when it will be measured. The latter are the questionnaires or other tools used to collect monitoring data.

- Monitoring: The use of the tools and methods described in the indicator matrix to collect and analyse data and determine performance.

- M&E information management: A system to ensure M&E data is maintained and accessible. Such a system may include a results database where indicator performance is tracked; a filing system for reports, distribution lists, photographs and other documents; and a case management database to track beneficiary engagement. An information management system can support an organisation’s assertion that it knows who received assistance.

- Evaluation plan: Evaluations look at a programme’s longer-term outcomes and impact. All programmes should have an evaluation plan, including a timeframe for evaluations, and their scope, purpose and funding sources.

- Staff: M&E requires enumerators to conduct interviews and collect data among the targeted communities; analysts to convert the raw monitoring data into indicator results and set them in a meaningful context; and management to be accountable for reporting requirements and use of the indicator results to improve programme design. Enumerators and analysts may be dedicated M&E staff or drawn from programme teams.

- Contribution analysis: If it is not possible to measure certain high-level indicators directly, a set of testable logical statements could be developed that demonstrate the programme’s contribution to them. If, for example, an organisation purchases tents and distributes them to people who do not have shelter, and those people use the tents, it can reasonably conclude that the tents have made a positive contribution to protecting the recipients from the elements. Contribution analysis requires a carefully thought-out results framework. Read more about contribution analysis here.

- Triangulation: Using various sources of data about the same indicator reduces the risk of poor quality and potentially misleading data. Photographs of aid distributions help to triangulate beneficiary lists, for example, and focus groups can be used to triangulate outcome indicator surveys.

- Sample size and randomisation: The careful selection of respondents can produce data and analysis that can be extrapolated to apply to all beneficiaries. Samples need to be sufficiently large, and all beneficiaries must have an equal chance of being included in them. Investing in rigorous and robust sampling methods will greatly increase the quality of M&E data. Read more about sampling here.

- Mobile data capture: If enumerators capture data on a mobile device rather than on paper, records can be time, date and location stamped. This information allows supervisors to confirm that sampling methods were properly implemented and identify other data quality issues. There is also less risk of transcription errors or manipulation because the data-entry step from paper to digital is eliminated. KoBoToolbox is a mobile data capture platform in use among some humanitarian organisations and offers many data capture tutorials.

- Supervision: Remotely managed programmes require more supervision, particularly to ensure M&E quality. Supervisors are needed to oversee data collection, clean data and ensure reporting and results make sense. This means investing in more staff hours and more dedicated staff to review reports and data from the field.

- Feedback mechanism: This provides a way for beneficiaries to submit independent comments on programme performance. Feedback mechanisms are difficult to put in place in areas where access is constrained, but when they can be implemented, they are a powerful way of learning about programme quality and triangulating M&E results. Read more about this in this paper from ALNAP.

- “Independent” monitoring: Bias is always a concern, and a genuinely objective assessment of project performance can be useful. True independence, however, can be difficult to achieve, particularly in areas where access is constrained. Focusing on independence or engaging independent monitors may simply exchange one set of biases that are easier to anticipate for another that is harder to quantify.

PCM and counterterrorism risks

PCM guidelines can form one component of a risk management framework for addressing counterterrorism issues, helping organisations to identify, evaluate and mitigate potential risks effectively throughout the different PCM phases.

This practical guide to PCM and counterterrorism risks draws on content from this toolkit. It outlines the origin and impact of counterterrorism measures and proposes actions for humanitarian organisations to consider throughout the programme cycle to help identify, manage, and mitigate counterterrorism-related risks.